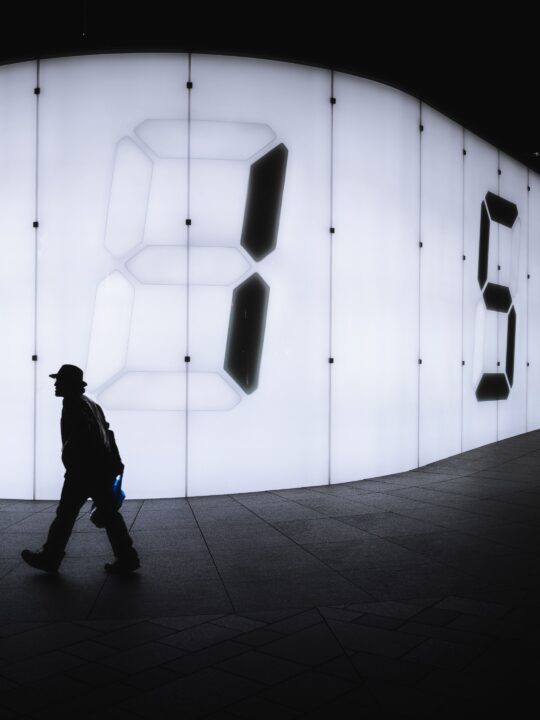

Are the numbers lying to you?

For this month’s installment of Behind the Data, we welcome a guest article from multi-award winning market researcher Suzanne Lugthart. Having worked for ITV, eBay and Rightmove, and now running her own consultancy Fathon Research, Suzanne’s mission is to root out the truth, and challenge falsehoods. In a world of misinformation, Suzanne champions accuracy in research – not taking numbers at face value whenever they appear online, and ensuring that data is interpreted accurately and meaningfully.

Social media and the democratisation of data have given us all greater access to information and the means to share it. Whilst this has it positives, it leaves one burning question: how do we know what we are reading is actually true?

Here are a few simple ways to check.

- Use your gut: does a number feel right?

The menopause finally is getting some well deserved attention, but it is often accompanied by a claim that as many as 13 million women are being failed. It’s a number that emerged in 2015 and doesn’t appear to have ever been challenged. So let’s just stop and think about 13 million for a moment.

According to ONS there are around 25 million adult women in England and Wales. Is it really likely that more than half are experiencing menopause at any one time? The source of the number has proved difficult to track down, but it looks like the original source counted all women aged between 40-75. So it needs to be made clear that this will include both pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women. A better estimate of women who might be affected by menopause is a still significant 3.3 million.

It’s a great example of how, once numbers find their way into the conversation, no one ever goes back to see if they’re actually true (a bit like the £350m a week that appeared on the side of a bus). These inaccuracies often mean that those genuinely affected by the issue, which is still a huge number, don’t receive proportionate attention and support.

Guardian headline from 2015

2. Is it just a spurious correlation?

A lot of published research draws conclusions based on correlations. But these need not necessarily imply causation. After all, there is a close statistical correlation between swimming pool deaths in the US and the number of Nicolas Cage films, and between cheese consumption and deaths by entanglement in bedsheets. Here’s one of my favourite examples from peak COVID hysteria – the alleged link between baldness and severe COVID 19 which may have had follicly challenged men tearing what was left of their hair out at the time.

What the study was actually picking up on were 3 truths which added up to a causal fallacy. a) men were more likely to experience severe COVID than women (true), b) older people were more likely to experience serious symptoms than young people (true) and c) older men are more likely to be bald (true).

3. Are they talking actual risk or relative risk?

You’ll be familiar with screaming headlines telling you how your risk of something unpleasant can be increased vastly if you do something which is generally considered pleasurable. But those percentages are usually RELATIVE risk numbers. So it’s always a good idea to check out your baseline ACTUAL risk in the first place.

For example – and after checking it’s a causal risk in the first place – if research suggested that eating lobster could double your risk of a nasty disease, but the original risk was only 1 in a million (0.0001%), you might be tempted to take your 0.0002% chance on a seafood dinner. And risk is rarely universal. It usually varies by age or circumstances. Our risk of death, of course, as a rule increases as we get older.

Daily Mail headline

4. Check where they’re getting this rubbish from

A couple of months ago a study was published claiming cyclists wearing protective headgear are perceived as less human. You don’t need to dig very deep to see the serious flaws in this one.

First, this bit of “science” used a self selecting sample of people on Facebook. They were shown pictures of cyclists in a range of protective clothing and asked to rate them on the Insect Scale (no, I’d not come across that one in 25 years of doing this stuff). The Insect scale ranges from a cockroach at one end to an upright human at the other via something like a praying mantis.

The study concluded that 30% of ‘people’ feel cyclists are less than human. And that wearing any kind of protective gear dehumanises them even more.

At this point you start to wonder why anyone is even doing this research

As researchers, we have the skills to call out these falsehoods when they occur. Much of what we see in the media is deliberately designed to terrify people into action. In a world where peoples’ mental well being is being affected by what they read and hear, we should play our part to make sure we don’t just champion insights and universal truths, but facts too.

Back to articles

Back to articles