When metrics mislead

Lambert Quetelet was a Belgian astronomer, mathematician, statistician, and sociologist born in Ghent in 1796. His work transcended the boundaries of science and statistics, influencing the fields of public health, social science, and anthropology.

Quetelet’s journey toward developing what we now know as the Body Mass Index (BMI) was rooted in his broader quest to understand human characteristics and society through the lens of statistical averages.

Quetelet aimed to quantify the “average man” in terms of physical and social attributes, believing that this would help identify the underlying structures of society. His work laid the groundwork for the modern field of statistics and its application in public health and social sciences.

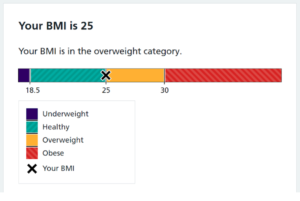

BMI is a thorny concept. One the one hand the measure is easy to understand and useful. It allows you to make population level comparisons quickly.

On the other hand: it is often misleading at the individual level. Any elite rugby player would be classed as obese.

Also, whilst it’s not a complex calculation, getting people to divide their weight (kg) by the square of their height (in metres) leaves plenty of room for error.

The main issue however is the absolute nature of BMI. If you are in the 18.5 to 24.9 range you are classed as being healthy. Someone who steps on the scales before lunch with a BMI is 24.9 is happy, and 10 minutes later after eating a boiled egg washed down with a glass of water suddenly reaches a BMI of 25 and is not.

Our world is nuanced, but BMI is not. All metrics lack context: they make us doubt ourselves, when really we should be looking at the issue in the round, with a healthy dose of perspective

When does a measure stop being a good measure?

New thinking on BMI comes from Dr Julian Hamilton-Shield. He suggests the waist-to-height ratio (waist in cm divided by height in cm) is a better indication of adiposity. Using this measure, weight should be less than half height (0.5).

No perfect measures

Yet, even Hamilton-Shield admits that the optimum way of measuring adiposity is to use an fMRI scanner to measure fat vs. mass bone mass in each person individually. This is obviously impractical!

But we need the best surrogate measure we can get. What’s easy gets used. What’s easy spurs action. Yet despite weight/height being about as simple as you can get – it still requires scales and a tape measure. This is where theory comes crashing into practice: 2 in 5 UK households don’t have a set of weighing scales. The public health challenge continues.

So to summarise, whatever the domain – whether you are interested in weight, customer satisfaction or a company’s valuation:

- No perfect measure exists

- Every measure has inherent dependencies and challenges

- Metrics are there to guide our judgment not to replace it

We should think of metrics as mere indicators – the first step in a journey of understanding

Back to articles

Back to articles