Transitions: a sweet spot for behaviour change

I moved house a couple of years ago — a new place, a new environment, a new commute. Old habits were broken, and new ones emerged:

- I didn’t have a recycling bin for two months, so I stopped recycling.

- Tesco was on my doorstep, so I stopped shopping at Sainsbury’s.

- I had to drive to the park to go for a run, so I ran less.

My attitudes hadn’t changed. I still believed in recycling, I still preferred Sainsbury’s to Tesco, and I still preferred to run every other day. But my behaviour had changed. The transition to a new environment moulded my behaviour. Environmental cues exerted a stronger influence than my beliefs or preferences.

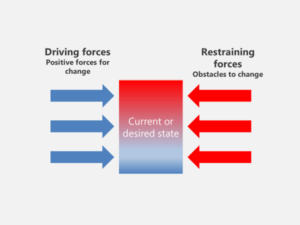

In the 1950s, pioneering psychologist Kurt Lewin posited that behaviour is held in equilibrium between driving and restraining forces. Daniel Kahneman described it as “the best idea I ever heard in psychology.”

For change to happen, the equilibrium must be upset. The theory says you must add conditions favourable to the change or reduce restraints. In practice, if you want to change behaviour, rather than increase driving forces (arguments, incentives and threats), you should diminish restraining forces (barriers, disincentives, and environmental cues). This is unintuitive.

Kahneman said, “A lot of things can be described as an equilibrium between driving and restraining forces. Lewin’s insight was that if you want to achieve change in behaviour, there is one good way to do it and one bad way to do it. The good way to do it is by diminishing the restraining forces, not by increasing the driving forces…”

To design a behaviour change intervention, start by asking “Why aren’t they doing ‘it’ already?” rather than “How can we get them to do ‘it’?” The tactics should focus on making it easier for people to behave the way you want. This is almost always about controlling the environment — for example, giving me a recycling bin the day I move in.

Research, of course, has a role to play. To understand restraining factors, we need to look at the situation from an individual’s point of view. This is about mapping behavioural patterns (revealed preferences, environmental cues, triggers) rather than ask/answer research.

Any transition can be seen as an opportunity if you’re looking to change behaviour. Moving home, changing job, and buying from a category for the first time are all chinks in the armour: our habit-formed behaviour breaks down, and there is a chance for change. Targeting interventions that remove restraints here (e.g. recycling bin, auto-enrolment to pension, offering a repeat subscription) means positive forces for change can prevail.

This all provides food for thought:

- Think about the lived experience of your customers. What transition points are relevant?

- What barriers could you remove to encourage people to change their behaviour?

- How might a change to environmental cues affect decision-making in your category?

Nudging modern attention: How streaming platforms can make remembering easier

A new appetite: How FMCG brands can innovate for the GLP-1 consumer

Tapping into “cosy season” with simple seasonal wins for retailers.

Back to articles

Back to articles